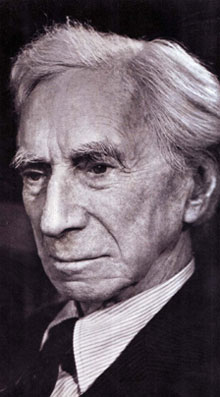

Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century. Together with G.E. Moore he founded the movement of analytic philosophy, according to which philosophical problems were genuine scientific or conceptual problems capable of precise and rigorous solutions.

Russell made extensive contributions to logic, epistemology, metaphysics, and philosophy of language. His most important work was completed with Alfred North Whitehead: Principia Mathematica (1910-13), a systematic presentation of a logical system in which arithmetic and set theory and parts and analysis (and in principle all of classical mathematics) were consequences of definitions using logical deduction alone. In this sense Russell and Whitehead claimed to vindicate the logicist conception of mathematics, as articulated by Frege and by Leibniz before him. Logicism continued to be central to Carnap’s thinking and a source of contention between Carnap and Quine.

In philosophy of language Russell’s theory of definite descriptions illustrated a more general and important distinction: the difference between logical and grammatical form. Thus the logical form of ‘the present King of France is bald’ is that there exists something that is a King of France, that this something is identical with everything that is a King of France, and that this something is bald; the key to reference is the use of existential quantification and relative pronouns -- the bound variable. The sentence is straightforwardly false, whereas hitherto it had seemed that there must be something corresponding to the King of France for the sentence to have any meaning. Russell’s analysis of reference played a central role in Quine’s philosophy of language and philosophy of science.

In The Analysis of Matter (1927) Russell drew the further conclusion that all scientific knowledge was knowledge by description and that no acquaintance with its objects was possible: in consequence he argued that scientific knowledge can only consist in the logical structure of things, not the natures of things in themselves, echoing Kant and neo-Kantian empiricists like Helmholtz, Hertz, and Poincaré . Structuralism remained a central theme in logical positivist and logical empiricist writings, and continues to dominate debates about realism today.

Russell was educated in Cambridge, where in 1899 he was appointed lecturer at Trinity College, counting Ludwig Wittgenstein as among his students. He was dismissed for anti-war protests in 1916, actions for which he was eventually imprisoned. In addition to continuing his philosophical writings, he became a prolific writer on a host of social issues, in education, marriage, religion, and politics, in recognition of which he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1960. From 1955 until the end of his life he was deeply involved in the anti-nuclear arms movement, the co-author of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto and the first president of the Campaign for nuclear disarmament.

Links

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Russell >

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Logical Atomism >

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Principia Mathematica >